AIER Board member Keith Harvey

[An edited version of this article appears in the journal Workplace Review Volume 8/2 Winter 2017 and is copyright to Thomson Reuters. The article below is the original unedited article.]

Recently, I chanced upon an old book — Australian Party Politics by James Jupp — published in 1968. It said:

“Australia has always had a high level of unionisation. This has been maintained by the arbitration system, by legal preference to unionists and, in Queensland, by compulsory unionism. There are more than two million union members, representing 56 per cent of the labour force”. [1]

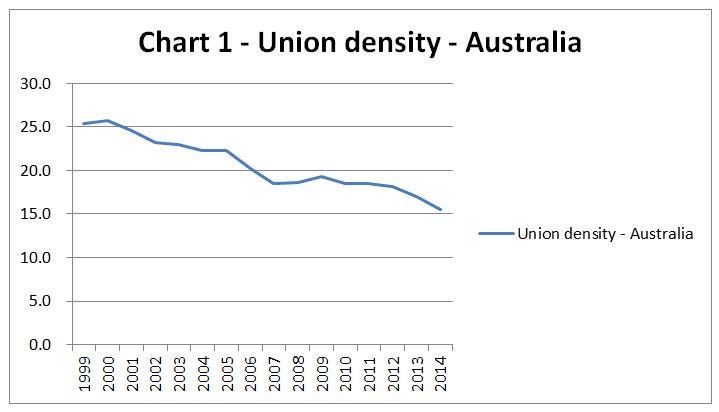

Over recent decades, the proportion of union members in the workforce has been steadily declining. [3]

It appears that union density peaked at nearly 65% in 1948, subsequently declined during the 1950s and 1960s — then rose again strongly in the 1970s and has declined since about 1986, halving over the past 25 years or so. The details of the decline hardly matter — the overall trend is not in dispute. [4]

The average density figure masks some key breakdowns. Amongst public sector employees density is still a reasonably substantial 38.5% but in the private sector the number has collapsed to just 10.4%.[5] It is not hard to imagine that in the next data release that this number will have fallen to less than ten percent. [6]

Despite the lingering blue collar image of the union movement, women unionists now outnumber their male colleagues for the first time in raw numbers: 800,800 to 746,400, and are now two and a half percentage points more likely to be union members as a proportion of the workforce than are males.

By industry, the most highly unionised sectors are those with a strong public sector element: utilities (29.1%), public administration and safety (33.2%) and education and training (27.7)] followed by health and social services (21.1%) and transport, post and warehousing (19.6%). Unionisation rates in mining, manufacturing and construction — previously the heartland of the union movement — are 16.7%, 12.7% and just 9.4%. [7]

Remarkably, professional employees are the ABS occupational group now most likely to be union members at just under 20%, though they are followed closely by machine operators (17.7%). Community service workers are next at 16.4%.[8]

Reflecting these changing demographic trends, both the senior officers of the ACTU today are women who have backgrounds in professional health and social services industries: President Ged Kearney comes from the Nurses Federation and new Secretary Sally McManus was previously Secretary of the NSW Services Branch of the Australian Services Union a union with growing membership among social and community services sector employees.

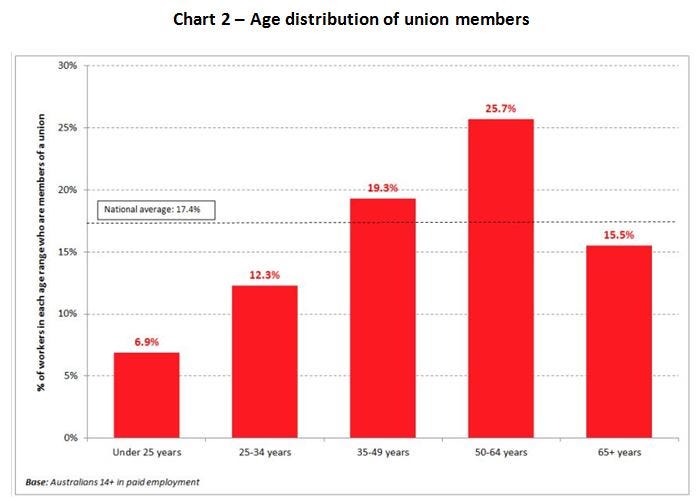

Of concern for the union movement is the age of union members. Unless older, aging union members are replaced, the decline in unionisation rates will accelerate.

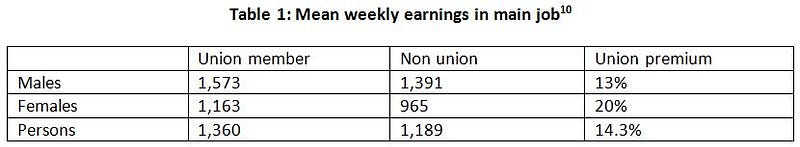

The good news for the union movement is that there is still a strong wage premium benefit in being a union member. The union wage premium for females is about twenty per cent; for males, 13 per cent.

Why has the rate of unionisation declined?

Unionism grew in the first half of the 20th century because there were strong structural supports and encouragements which fostered the growth of representative organisations of employees [and employers].

Compulsory arbitration of disputes and award making allowed unions to demonstrate to workers their ability to take effective action to establish decent wages and working conditions. Unionism was the mechanism by which the voice of workers was heard in industrial tribunals.

Unionism was considered by the Australian community to be a ‘public good’ to be encouraged. Until 1996, unions were able to apply for ‘union preference clauses’ in awards in certain circumstances. [11]

The extension of preference clauses to key clerical awards in the 1970s was responsible for the boost in union membership amongst white collar workers. Some employers were willing to enter into ‘point of engagement’ union membership agreements with unions to avoid preference clauses.

As ‘recently’ as 1970 the McMahon Liberal Government was willing to introduce payroll deduction facilities for federal public servants which, along with the pro-union stance of the subsequent Whitlam Labor government, encouraged the growth of public sector unionism.[12]

The trade union movement considered the Fraser Government to be hostile to unionism but in retrospect it appears to have been more than benign. The union movement appeared to reach the height of its powers during the Hawke/Keating Governments of 1983–1996 — the period of the Prices and Incomes Accord. However, the decline in union density also began in this period.

During the Accord period the ACTU sought to strengthen unionism through amalgamations and by the process of union ‘rationalisation’. This did not arrest the decline in union density.

This time also saw the introduction of enterprise bargaining, initially opposed but later supported by unions. Many unions saw enterprise bargaining as an organising and recruitment opportunity and a means to demonstrate the power of collective action.

Enterprise bargaining became a two-edged sword: the Keating/Brereton reforms to industrial legislation introduced a ‘non-union’ stream to bargaining, removing the central position of unions in the bargaining process and allowing employers to ‘bargain’ directly with employees . [13]

During the 1980s, the national consensus supporting unionism and arbitration as a ‘public good’ began to break down. Employers went on the offensive, seeking to de-unionise not only white-collar areas of employment but also union heartland areas such as mining. The names Dollar Sweets, Mudginberri ,the SEQUEB dispute and CRA/Robe River reflect only the most prominent attempts by employers to attack and defeat unionism.[14]

In 1996, the newly elected Howard government began an all-out offensive against unionism, beginning with the Workplace Relations Act [15] and culminating in the WorkChoices Act. [16]

The Howard Government’s attack on unionism was multi-pronged. It was spear headed by statutory individual agreements [AWAs] which replaced all forms of collective instruments and included

- taking the timing of annual national wage claims out of the hands of both the ACTU as applicant and even out of the hands of the Industrial Relations Commission.

- restricting the ability of unions to take industrial action

- offering a form of non-union entitlements enforcement through a reasonably well resourced government agency (the Employment Advocate)

The limited forms of ‘preference to unionists’ available were removed by the Workplace Relations Act 1996. [17] Freedom of Association (FOA) has been enshrined in legislation but equally so has a freedom of ‘non association’. FOA, which was originally designed by the International Labor Organisation to support unionism, is today in the Australian context almost as equally used as a weapon against unionism and in support of the rights of non-unionists.

The Howard government’s objective was to marginalise unions. While this eventually led to the downfall of the Government and lost the Prime Minister his seat, the union movement had a difficult time negotiating a new policy with the ALP — which backtracked on key agreed elements late in the election campaign. The new Fair Work Act retained a number of key features of the previous regime, although it abolished AWAs. [18]

Unionists were left with the feeling that the incoming ALP government did not want to be seen to be close to the union movement. In his election campaign in 2008, Barak Obama declared “I believe in unions” [19] but nothing of the sort was heard from Kevin Rudd before or after he was elected.

Tony Abbott appointed a Royal Commission to inquire into the activities of some trade unions. This was designed presumably to build an argument for tighter controls on the activities of unions. The now-legislated Registered Organisations Commission [which began operating on 1st May 2017] was however in the Coalition’s policy from 2013. [20]

Throughout this whole period the rate of unionisation has continued to decline. Measures adopted by the union movement such as Organising Works — an attempt to create a new cohort of young unionists adept in organising — and a range of organising efforts in sectors of the ‘new economy’ have failed to reverse this declining trend.

The impact of declining unionisation rates

However, over the past two years or so, Australia has been rocked by a series of public wage scandals affecting employees in a range of industry sectors. A question often debated in the 1970s was “do unions have too much power?”.[21]

Now the question could hardly be asked in a workplace setting. The wage scandals in fast food, retail, agriculture and elsewhere point only to one thing: not only do unions have limited power, without unions employees increasingly have none. When vulnerable immigrant workers are forced to lie about their hours of work or hand back in cash part of their earnings there is a serious problem in this country.

Wage growth is at record lows in Australia and in other developed economies. [22] This is increasingly being blamed for declining household incomes, dragging down taxation revenue to the government, increasing income inequality and even poor investment returns.

Recently, the ANZ bank issued a warning that “soft wage growth was an important economic risk” since wages were growing more slowly than inflation leading to the risk of mortgage stress. [23] Wages growth has been de-linked from productivity growth and the corporate share of national income increasing at the expense of that of labour. [24]

Income inequality has been held to be a drag on world economic growth [25] and a reason for the election of Donald Trump and support for Brexit. The role of declining unionisation rates in increasing inequality has been noted. [26]

Following a boom in enterprise agreement making in the initial years of the Fair Work Act, the number of agreements being made is in significant decline.[27] Many employees are languishing under ‘zombie’ agreements; that is agreements which have passed their nominal expiry dates but which have not been replaced and are no longer delivering wage rises.

The benefits of enterprise bargaining now appear to have been exhausted. There seems little incentive to bargain further and as 90% of private sector workers are non-union, unions have no power to press a bargaining campaign.

Incoming ACTU Secretary Sally Mc Manus may well be right to say that the benefits of the micro-economic reforms of the Hawke/Keating years have been exhausted and not equally shared. [28]

Concentrating solely on the rights of individuals rather than on the power of the collective provides little real benefit for workers as a whole. Individuals may assert their existing rights (won by others) but are unable to improve standards overall.

As an example, consider the recent equal pay case for social and community services employees. The granting of pay equity is provided for in the Fair Work Act, but requires an application by someone to achieve it. That someone was five unions who employed barristers and other staff to assemble and present evidence via scores of witnesses and in other ways. The case ran for two years or so and cost hundreds and thousands of dollars of union members’ money. [29]

The successful outcome was a positive benefit to the employees, and to the sector itself and therefore its clients and society as a whole. The application was supported by key employers in the sector [other employer organisations were wary of the flow-on effects] and by the Federal and Labor State governments.

Unorganised workers could not have run this case. Non unionists contributed nothing to it. There is no ‘public good’ to be found in non-unionism.

What needs to be done

In recent years, unions have tried to arrest the decline in unionisation. Financial scandals in some unions such of the HSUA, the NUW and others have not helped the image of the union movement, nor has some of the agreement making practices uncovered by the Royal Commission. Union officials must always carry out their duties in trust for and only in the best interests of their members.

Even without the existence of scandal, unionism has been declining in significance. It may no longer be within the power of the trade union movement alone to reverse this trend.

This is now a matter in which society as a whole must play a role, both in the national interest and in the interests of working people. The economy is not hindered by a strong union movement. Vibrant, democratic and active unions can help drive better and more productive workplaces through decent work and high productivity and performance.

The race to the bottom in wages and conditions is not serving Australia well. Cheap pizzas based on the exploitation of vulnerable workers are not necessary.

Unionism is not a selfish act, but a selfless one. It was long recognised as a public good and a social utility to be encouraged. It still should be.

The Fair Work Act needs to be amended to re-introduce as an objective the encouragement of an active and involved workforce and representative bodies of workers. Freedom of association should operate so as to encourage the right to form and join unions and to bargain rather than treating free-riding as an equally desirable outcome. The role of arbitration of all award and workplace disputes must be re-established.

To create the political space in which such actions can be taken, politicians of all parties need to recognise the value of unionism to Australia and to speak up to support this value. Employers and employer organisations need to work co-operatively with their employees and their representatives to create decent workplaces with decent wages and working conditions. A low wage, low productivity economy serves no one in the long run.

References

[1] Jupp, J, Australian Party Politics, Melbourne University Press, Second Edition 1968, p31

[2] ABS, Characteristics of Employment, Australia, August 2016, Table 16.1, Employees and Owner Managers of Incorporated Enterprises in Main Job. The ABS also has another measure of union density which includes all ‘Employed Persons’. This data set includes owners of unincorporated enterprises. By this measure, union density is 13.2%.

[3] Table constructed from OECD data: https://stats.oecd.org/Index.aspx?DataSetCode=UN_DEN

[4] But if the reader is interested in the details see: Bowden, B, The Rise and Decline of Australian Unionism: A History of Industrial Labour from the 1820s to 2010, Labour History, No 100 2011 pp 55 and ff; and Bramble, T: Trade Unionism in Australia: A history from flood to ebb tide, Cambridge University Press, 2008

[5] ABS, op. cit., Table 16.1

[6] It is already less than ten per cent if the measure is all Employed Persons: ABS, op. cit., Table 18.1

[7] ABS, op.cit., Table 18.1. Note that these are all Employed persons figures, the only sector breakdown available in the most recent release of data.

[8] Ibid

[9] Roy Morgan Research: http://www.roymorgan.com/findings/7104-who-are-australias-union-members-you-might-be-surprised-201701101609

[10] ABS, op. cit., Table 19.1

[11] CONCILIATION AND ARBITRATION ACT 1904–1973 — SECT. 47.

[12] Bowden, op. cit, p 67

[13] Industrial Relations Reform Act 1993: https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2004A04653. S.170NA

[14] Bowden, o[.cit. pp 70–1

[15] Workplace Relations Act 1996 https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2006C00104

[16] Workplace Relations Amendment (Work Choices) Act 2005 https://www.legislation.gov.au/Details/C2005A00153

[17] See Schedule 16 Explanatory Memorandum for Workplace Relations Act: http://www.aph.gov.au/Parliamentary_Business/Bills_Legislation/bd/BD96/96bd96#16

[18] https://www.legislation.gov.au/Series/C2009A00028

[19] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kJ3ibE6LtEE

[20] The Coalition’s Policy to Improve the fair Work Laws, May 2013, p 6

[21] According to the ANU Trends in Australian Political Opinion Results from the Australian Election Study 1987–2016, 82% of people held this view in 1979, p 84

[22] http://www.abc.net.au/news/2017-02-22/wage-growth-remains-at-record-lows/8293704

[23] ANZ warning on wage growth, The Age, May 3, 2017, p 23

[24] ACTU [Matt Cowgill] A Shrinking Slice of the Pie, 2013 http://www.actu.org.au/media/297315/Shrinking%20Slice%20of%20the%20Pie%202013%20Final.pdf

[25] See for example International Labour Organization, International Monetary Fund, Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development and World Bank Group Bank Income inequality and labour income share in G20 countries:Trends, Impacts and Causes. Prepared for the G20 Labour and Employment Ministers Meeting and Joint Meeting with the G20 Finance Ministers, Ankara, Turkey, 3–4 September 2015

[26] Ibid, pp 17–18

[27] See Trends in Federal Enterprise Bargaining — December 2016, Table 4 https://docs.employment.gov.au/node/37941/

[29] https://www.fwc.gov.au/documents/sites/remuneration/decisions/2011fwafb2700.htm

Text © Keith Harvey 2017