Inspired by Ron’s declaration at last year’s debate, the 2017 topic was “The system is broken. What is the fix?”

The Institute’s seventh Ron McCallum Debate was another great success with a robust discussion about the future of regulating work. Former FWC and AIRC President Geoff Giudice chaired the debate, with the following speakers offering their perspectives on the topic:

perspectives on the topic:

- Emeritus Professor Ron McCallum

- Jo Schofield, United Voice

- Stephen Cartwright, NSW Business Chamber

- Sarah Kaine, UTS

- Lina Cabaero-Ponnambalam, Asian Women at Work

Watch the Debate

While there was general agreement among the panel that the workplace relations system is broken, the speakers provided a range of perspectives on why and a variety of prescriptions for fixing it.

This year the debate was structured around two questions:

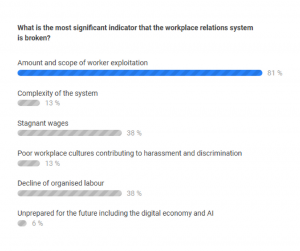

- Do you think the workplace relations system is broken? If so, what for you is the most significant indicator that something is wrong? If not, what is working best?

- If there was one thing you could fix or improve first, what would it be?

Each speaker addressed each question in turn.

Starting off the discussion Jo Schofield from United Voice argued our workplace relations system, like many other institutions, has been captured by neoliberal ideology. This has led to a tension in balancing microeconomic reform on the one hand and addressing the needs of workers through a system of rights and protections, including the right to join a union and to organise. The microeconomic side of the equation has won. The system is increasingly out of reach and irrelevant for large numbers of workers. Jo went onto argue that a key indicator that the system is broken is that the system no longer operates as a place where the rights and protections of workers can be upheld or improved beyond a minimal safety net. Jo also touched on worker exploitation, wage stagnation, the individualized gig economy, supply chains and the ongoing gender pay gap as challenges for the system.

Stephen Cartwright addressed the question comparing Australia’s workplace relations system to other comparable nations. He cited the Global Competitiveness Report from the World Economic Forum pointing to three measures where Australia ranks low: cooperation in labour relations; flexibility of wage determination; and hiring and firing practices. On that basis he concludes our system must be broken. Stephen then went on consider whether the system is meeting its own objectives based on the Fair Work Act: safety net of minimum conditions of employment – too many awards, fail; a system of enterprise bargaining – use of EBAs is in rapid decline, fail; individual flexibility arrangements – fail, biggest indicator the system is broken; protection against unfair dismissal – pass; freedom of representation – pass. He finished by mentioning two other indicators: wage stagnation, occurring in a system without individual flexibility where employers are going back to using awards; and while overall unemployment at 5.5% is ok youth unemployment has continued to deteriorate and the system is not helping address it.

Sarah Kaine spoke next arguing that the system does not provide systemic support for the most significant component of workplace democracy – worker voice. That is the capacity of workers to have a meaningful say about the determination of issues that relate to their work. In fact she suggested “the current system actively silences workers – through restrictions to internationally recognised freedoms, discouragement of industry based bargaining and through marginalising workers who don’t conform to narrow definitions or fit historical categories.” Sarah went on to argue that “the current system perpetuates and exacerbates a power imbalance in which organisations manipulate their business structures to avoid responsibilities – be it through convoluted supply chains, franchising arrangements, or the mediation of work through digital platforms”. She concluded by noting that the most successful means of addressing that imbalance has been through the exercise of collective voice by workers.

Audience poll on why the system is broken

Lina Cabaero-Ponnambalam asked some of the women involved in Asian Women at Work if they thought the system was broken. They answered with a resounding Yes and asked Lina to tell some of their stories. Lina shared stories of women whose working conditions do not provide for dignity or social justice: women working in nail salons and not getting paid; women working in meat factories without the right protection; women trying to navigate job service providers while injured from work; and women who have to sign in and out to use the toilet. Lina concluded arguing that “the system is broken and it is breaking the lives of migrant workers. The system is broken and is depriving migrant women workers the right to be treated with dignity and respect, right to have a job, the right to have a safe and harassment-free workplace, the right to fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work, the right to have regular hours and security at work.”

Lina Cabaero-Ponnambalam asked some of the women involved in Asian Women at Work if they thought the system was broken. They answered with a resounding Yes and asked Lina to tell some of their stories. Lina shared stories of women whose working conditions do not provide for dignity or social justice: women working in nail salons and not getting paid; women working in meat factories without the right protection; women trying to navigate job service providers while injured from work; and women who have to sign in and out to use the toilet. Lina concluded arguing that “the system is broken and it is breaking the lives of migrant workers. The system is broken and is depriving migrant women workers the right to be treated with dignity and respect, right to have a job, the right to have a safe and harassment-free workplace, the right to fair day’s pay for a fair day’s work, the right to have regular hours and security at work.”

Ron McCallum agreed with almost all of what the previous speakers said. The system does require amendment. It is failing Australian workers and employers. He noted that wage stagnation is in many ways due to the fact that collective bargaining in failing. He went onto to propose that collective bargaining has really become an enclave of the public sector. Ron then went to suggest that our federal government and the opposition are failing us. Following the Productivity Commission report there has been very little amending legislation. No one has looked at the gig economy or collective bargaining or the award system. What he wants is more public debate and more thought coming from our politicians.

On the second question of what to fix first, Jo argued we need better political leadership and coherent public policy that integrates our workplace relations framework more closely with our social and economic aspirations as a country. A poorly functioning workplace relations system has severe human and social consequences. It shifts costs to other parts of the economy – welfare and health system for example. There are things we can do. One thing we need to do is to restore the system’s relevance to workers. For example, by ensuring stronger enforcement to address exploitation. Jo argued we also need to restore granularity to the system so it can be accessed by workers, that is, providing access for workers to be involved in decisions that affect them, including via their right to organise and take industrial action. She also noted we are missing something without state systems with the bureaucratic nature of the federal system. Jo concluded by arguing we need to address equity, including through minimum wages set at 60% of medium earnings.

Stephen spoke next noting Australia is a SME economy and suggesting the one thing he would do would be to create a set of fair and proper safety net regulations for small business and allow the use of the Australian Workplace Agreements to suit the needs of the business and each employee. He rejected the need for a “nanny state” to intervene. He noted that big business would oppose this suggestion as much as unions because they fear competitive advantage. But it is small business that innovates and is responsible for net job creation in NSW. We need to unlock their capacity to thrive and create new employment. He provided two examples: a café owner in a region with high youth unemployment who cannot employ people who want to work weekends but not weekdays without paying penalty rates; a helicopter maintenance business with very variable workload that used AWAs to manage the fluctuation, now the flexibility is not available.

Sarah picked up on Stephen concern about the “nanny state” but from a different perspective. She is concerned it is not big enough. The state is simply not able to deal with the scale of the compliance issues we are seeing. Sarah went on to promote the idea of “co-enforcement” as her one thing we should change. She noted that co-enforcement’ is when “state agencies actively partner with worker organisations – be they unions or community based worker centres (just like Asian Women at Work) in a way that ‘leverages the non-substitutable capabilities of state and society’. That is there are some things states are good at and some things other organisations are good at and we should maximize the capacity of all stakeholders. Sarah provided the example of the Cleaning Accountability Framework. In conclusion she noted that “Co-enforcement is based on the recognition that there is no substitute for authentic worker voice, that the representatives of workers have a legitimate role at a local and industry level” and that “if we are talking about changing the system we need to consider not just how to encourage voice but how to amplify it.”

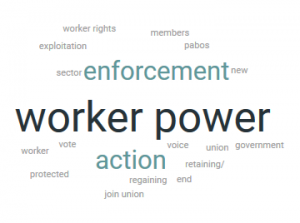

Audience poll on what needs to change

Lina spoke to not wanting the stories she told before to be told and retold forever and we do not want women to accept that exploitation in the workforce is the new norm. Women told her that what they really want fixed are their bosses. They want their bosses to follow the law. The Fair Work Ombudsman must have more proactive inspectors doing investigations, and need bi-lingual inspectors. Unions need greater right of entry and enforcement powers. Asian Women at Work have a good relationship with unions, particularly the TCFUA. Competent trade unions are the best part of the workplace relations system. Lina also wants unions to have bi-lingual organisers.

Lina spoke to not wanting the stories she told before to be told and retold forever and we do not want women to accept that exploitation in the workforce is the new norm. Women told her that what they really want fixed are their bosses. They want their bosses to follow the law. The Fair Work Ombudsman must have more proactive inspectors doing investigations, and need bi-lingual inspectors. Unions need greater right of entry and enforcement powers. Asian Women at Work have a good relationship with unions, particularly the TCFUA. Competent trade unions are the best part of the workplace relations system. Lina also wants unions to have bi-lingual organisers.

Ron finished this part of the event arguing that the one thing needed is to improve collective bargaining. Collective bargaining not only allows for good outcomes for employers and employees but it provides for workplace democracy and voice at work. Ron argued that bargaining is not just for employees, but also that workers in the “gig” economy and independent contractors should be allowed to engage in collective bargaining. The problem is who pays for it. The union movement is spread very thin and bargaining fees are outlawed. What if we thought laterally – why not get the government to pay, say $10, for every employee and employer to their bargaining agent for a successful agreement. We need to explore incentives for bargaining and the making of worthwhile agreements, that give people dignity and voice, and address wage stagnation. In conclusion, Ron referred to the British Employment Rights Act that creates an intermediate category of employee that get access to some of the minimum standards as an example of the type of thinking we need to pursue.

The contributions by speakers on the two questions of the Debate was followed by questions from the audience. We used slido.com to elict questions and to poll the audience on their thoughts on the topic. Questions covered issues to do with bargaining, including changing the scope of bargaining, and the failure of the low-paid bargaining stream; enforcement and how it could be improved; how to improve public policy development in context of polarized nature of the debate on workplace relations; role of other advocacy organisations in workplace relations, like GetUp; the relevance of the right to strike; link between pay increases and consumer spending in the economy; whether the concept of labour and capital has changed; and the process for terminating enterprise agreements.

AIER thanks all the participants for an excellent discussion. This year’s debate fully lived up to AIER’s hopes for encouraging public debate on key issues of workplace relations.

Watch the video of the event

Read AIER’s Discussion Paper highlighting a number of reasons why we think the system is broken and summarizing different approaches to fixing it, including our “New Architecture” project.